Poland and swordbearing tradition

March 19, 2018

"Starzy Poliacy jeśli pieszo z kordem chodzili, tedy za niemi tudzież pacholie abo giermek z mieczem szedł, [...]"

"The Poles of yore, if they were on foot with the saber (kord), then either a boy or a squire would walk behind them and carry a sword [...]"

This short sentence from the Stanisław Sarnicki book of officers (‘Ksiegi Hetmańskie’) from the 1580s is just a glimpse into a much greater tradition once cultivated in Poland.

There are several traditions connected to the idea of swordbearing in Poland.

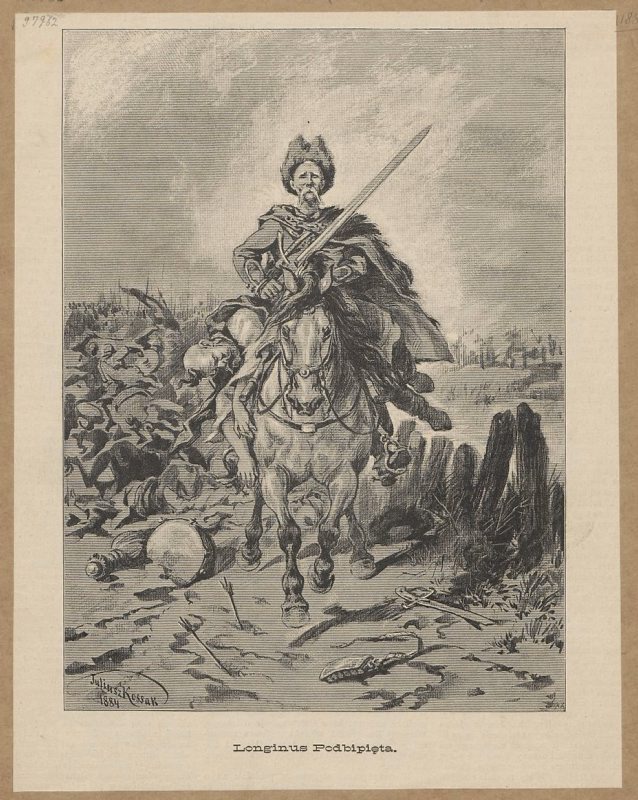

The earliest is the tradition of the ensifer or gladiifer, a court official, whose duty was simply to carry a sword in front of the king on special occasions. It is known from the 11th century in Poland, but the tradition developed fully in the 16th and 17th centuries, when some higher officials officially had a select man carry a sword behind them into battle or on other occasions. An example of that could be a painting by Wociech Kossak showing Kazimierz Pulaski (the first picture) accompanied by a man on his left carrying a sword. This custom was naturally portrayed in Polish literature, for instance in one of the prominent works by a celebrated Polish 19th-century poet, Adam Mickiewicz –„Pan Tadeusz”. In this story, such honorary office is held by Gerwazy, one of the main protagonists (the second picture).

Secondly, in the 16th century, Polish nobility was most proud of their knightly ancestry, which fuelled a tradition that was often observed throughout Poland: some Polish nobles carried greatswords with them (naturally, they were actually taken care of by a squire or a boy). It particularly interesting, since in contrary to the previous tradition, the nobles themselves carried a representative and elegant weapon by their side (most often a lavishly decorated saber) or simply a cavalry saber considered a symbol of nobility, whereas the squire by their side would carry a fully battle-ready and functional greatsword. The aforementioned manual by Sarnicki underlines that against, for example, the Italian sidesword it is better not to use a saber. Instead in order fight against it, it was obvious to just reach for the greatsword one’s squire was carrying. There are many depictions of such swordbearing squires throughout history (pictures).

In the literature of the period, that is in Jan Chryzostom Pasek’s memoirs, one can easily find certain Kasztelan Zakromczyński, a very special character, who had a swordbearer boy next to him and was known for his very high prowess in the use of the saber and the sword. He was also the only person practising with the sword mentioned throughout the entire book. He reportedly used a very specific flourish from time to time, which he performed to the sound of music.

In the later literature, the romantic period also provides us with another fictional, but clearly based on older traditions, example of a man with a sword of this sort. Longinus Podbipięta from the novel „Ogniem i Mieczem” by Henryk Sienkiewicz, being a man of great stature, carried a greatsword of a matching height. He too was known for great battle prowess, and reportedly the sword was passed on within his family since the time of battles with the Teutonic Knights. It must have been the last Polish-Teutonic War of 1511 to 1525, as such sizeable swords had not been not seen in the earlier periods (the picture before the last).

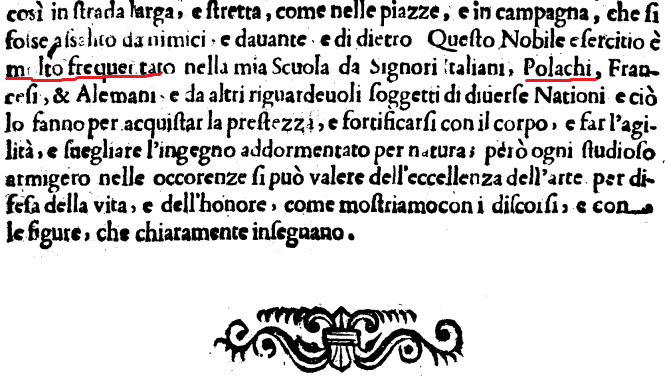

There is also a significant mention that should be underlined here, which comes from Francesco Alifieri’s treatise from 1653. He states in the foreword that he taught his art of the two handed sword to some Polish masters (last picture with text). It is nothing uncommon, as being a master of the Paduan school, he was very familiar with Polish nobles who back then would eagerly study at the town’s university.